Who do you say I am?

In the gospel reading today from Mark, Jesus asks his disciples, “Who do people say I am?” and their answers refer to the fierce warrior prophets, John the Baptist, Elijah or someone like Jeremiah. These were men fearful to look upon and listen to, who shouted dire warnings and condemnation at the people for their sinful ways and their abandonment of God. The people in his time perceived Jesus in the tradition of the prophets and saw him as a prophet. Jesus too spoke of himself in this light: “Prophets are not without honour, except in their hometown.” (Mark 6:4) In the opinion of others and in his own consciousness, Jesus was like the prophets of the Jewish Bible. Like them, his calling and passion as a prophet came out of his experience of God. When Jesus asks the disciples, “who do YOU say that I am?” Peter’s answer rings out loud and clear: “You are the Messiah.” In Luke’s version of this incident, he adds the words, “of God,” and Matthew’s version adds, “Son of the Living God.”

The changes in Peter’s cry from Mark to Luke to Matthew reveal the developing tradition around Jesus and points to the early Christian community’s central conviction, that the Jesus whom they experienced and remembered is the decisive revelation of God.

In Matthew Jesus confirms that Peter’s insight has come from divine inspiration: “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven.” Jesus affirms that he is not the kind of Messiah that other people, “flesh and blood,” imagined and longed for. Throughout the gospels Jesus teaches his followers that he is a different kind of Messiah than expected, than we often still expect; he is “gentle and humble in heart,” not the warrior Messiah long hoped for by the children of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Moses, a hero to lead in battle and victory against oppressors. In Mark’s telling of this moment, Jesus “began to teach them that the Son of Man must undergo great suffering, be rejected by the elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again.” Notice Peter’s reaction: “Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him,” no doubt explaining to Jesus that the scenario he outlines just won’t do. In Matthew’s gospel Jesus praised Peter for his insight that Jesus was the long-awaited Messiah: “Peter, you are favoured indeed, for you did not learn that from mortal man; it was revealed to you by my heavenly Father.” But now, it is Peter’s turn to be rebuked for “thinking as men think, not as God thinks,” because he does not understand or want to accept the type of Messiah which Jesus is called to be. Peter was no doubt hoping, as were many of his contemporaries, for a warrior Messiah who would free the Jewish people from bondage to Rome, just as Moses had led the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt.

Christ is not a warrior king, but a servant, the image coming from the second half of Isaiah, one who identifies and suffers with the oppressed, one who does not resort to violence to set his people free. We’re always living in violent times, as the news certainly makes quite plain. The familiar story of Jesus’ birth emphasizes that he too was born in violent times; however, as the Christ he assumed the mantle of a suffering servant, offering freedom and love. He was not a warrior but a shepherd, and his model of and for peace still waits to be unlocked on this “rock” by his people who have been given “the keys of the kingdom.” Jesus would have us follow his example to be good servants, to care and love all God’s people and God’s world, all of creation. Such a selfless sacrifice is graphically seen in Christ’s passion and death, and in the sacrifice of Christian martyrs, people called to stand up for their beliefs, but the majority of us are called to practice Christ’s way of loving in our lives, “daily,” as Matthew and Luke put it, and that too requires that self often be denied. To practice love requires that we put others before ourselves. In so many troubled relationships or situations, such as the violence erupting during this election campaign, the root cause is so often a selfish attitude, or several selfish attitudes clashing head on, each person vying for self-interest. It takes a spiritual effort to lose self, to find within oneself patience, kindness, mercy, or compassion in the face of anger and violence. These ideals of Christian behaviour are not always attainable, but we are to strive to uphold such ideals in a world sadly in need of compassion and direction. Our model is the selfless sacrifice of Christ, the never-failing love of God, “who so loved the world that he gave . . . life.” To be a follower of Jesus is to live Christ’s way of selfless love so that others might live abundantly.

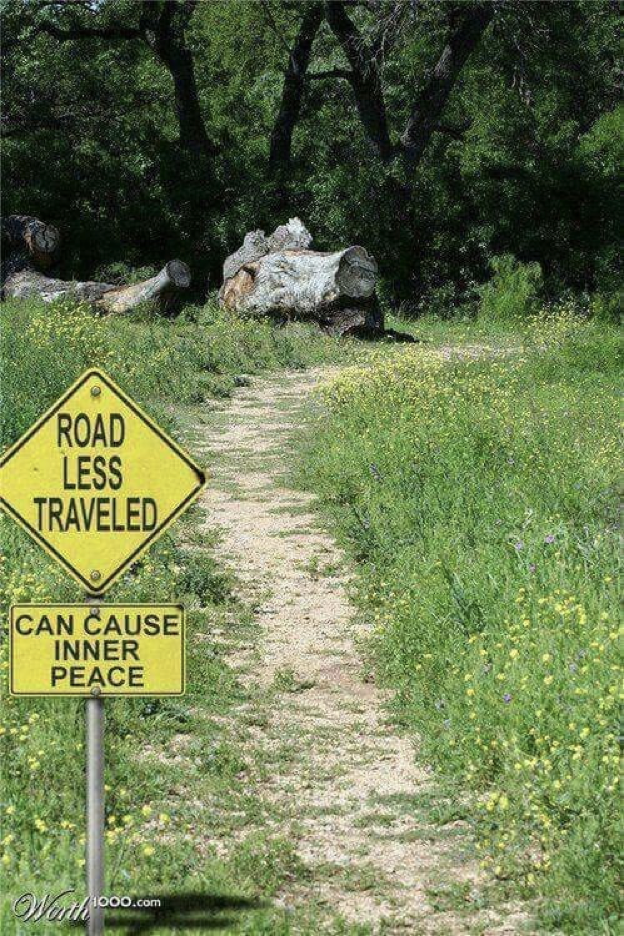

It is much easier, for writers and filmmakers—and political candidates for the highest office in the land—to attract audiences with adventurous tales of violent heroics. A story of spiritual strength and inner peace just doesn’t gain much notice. The newscast needs the excitement of violence to improve ratings, pictures of war and rumours of war, but the quiet peaceful diplomacy of men and women of God, like Desmond Tutu in South Africa or the Dalai Lama of Tibet, do not often or easily make headlines. Christ offers his followers a way to freedom and love, to fullness of life, when they work together, guided by his teachings and principles of peace and goodwill. Peace comes when we make choices in tune with God’s purposes. Peace comes when we are at peace, with God and ourselves. Taking the risk to “choose life” and dedicating ourselves to God’s service can at times be extremely difficult, but we who profess to follow the Master must keep striving, within ourselves, with each other, with our society and world, to follow the path of peace, to serve others in the name of freedom and love.